This is the second in a series of four blog posts on hydrologic restoration in Wisconsin. Read part 1, “How wetlands manage water,” and part 3, “Our legacy of wetland loss: Behind our water problems,” and part 4, “Fixing our waters: Community-led watershed-based hydrologic restoration in Wisconsin”.

How past actions are behind today’s water challenges

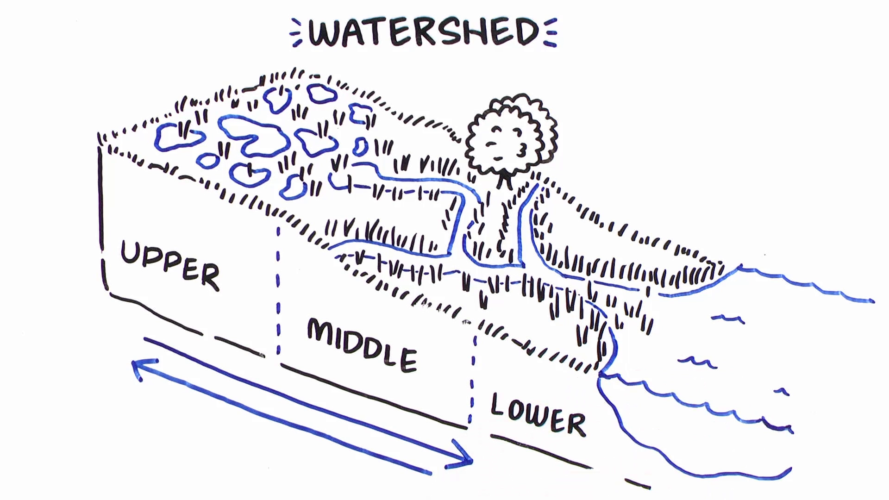

In “How wetlands manage water”, we outlined how water moves through a watershed and how wetlands help manage that water. An organized, connected system—the watershed— moves water from the top headwaters to the water body at the bottom. This is true even in what, today, are our most urban watersheds. Complex interactions involving geology, geography, weather, water, sediment, soil, vegetation, animals, and wetlands create our natural, healthy ecosystems.

An additional, though often unstated, element can also have profound influences on these interactions: human activity.

Pamphlets like this one explaining how to effectively drain wetlands were common in the early days of European settlement in Wisconsin and much of the Midwest.

As humans, we’ve been changing the way water moves through our landscapes—the hydrology—across the globe for millennia. Over the centuries, we’ve become more and more effective at altering our natural landscapes to suit our needs. Our actions change the course of water movement—sometimes intentionally and sometimes unintentionally—and these actions can have consequences not only where they occur, but also many miles downstream.

When we look at water movement in Wisconsin—once an incredibly wet and wetland-rich state—we see the effects of human influence nearly everywhere. Though our modern communities and economies are an important result of these alterations, the consequences of our actions are also causing many of today’s water challenges.

So, what have we done and how have some of our actions changed the way water moves?

We’ve drained wetlands.

Generally speaking, many of our early development actions in Wisconsin were designed to make places less wet so the land could accommodate human use, including agriculture and urban development. To make places less wet, we started with the easy stuff—the elimination of nearly half of our state’s wetlands, especially upper watershed wetlands, through thousands of miles of drainage ditches, tiles, land leveling, and other practices.

When you make one place less wet, the water that was held in that place has to go somewhere else. Water previously stored in upper watershed wetlands, then, flowed down the watershed, leading to less storage in upper areas and more water in lower areas. Our upper watersheds became drier and our lower watersheds became wetter.

We’ve helped water move faster.

We’ve moved water further and faster downstream by ditching wetlands and channelizing waterways. Streams, creeks, and rivers were moved to the edge of their floodplain valleys, and levees were placed to keep them there. Floodplain disconnection, combined with the removal of upper watershed wetlands, not only caused water to move downstream faster, but also increased the erosive power of that water and created unnaturally higher and flashier flood peaks.

We’ve built cities, roads, and other infrastructure.

We’ve filled large wetlands in some lower watershed areas to accommodate our communities. Cities such as Milwaukee, Madison, Green Bay, Superior, and many others developed in locations that were very wetland rich. We’ve built roads and highways across the state, bisecting wetlands and diverting water in new directions, sometimes even into other watersheds. In many places, our roads act like dams or levees, blocking the historic natural flow.

Cumulative impacts: one plus one can equal three.

In most watersheds, combinations of many factors have altered the way water moves across the land. Often, these alterations result in damaging feedback loops that lead to further disruption of hydrology. For example, the more we drain upper watershed areas, the more we need to do to bolster middle- and lower-watershed areas from the impacts of more and faster-moving water. The more our actions shift our water conditions away from their natural movement patterns, the more this damaging feedback cycle strengthens. Add more extreme storm events due to climate change on top of all this, and things can get out of control very fast.

Here’s an example of a damaging feedback loop: This ephemeral creek is disconnected from its floodplain wetlands—areas adjacent to the creek where water can spread out and slow down. Without the help of the floodplain, the fast-moving water from each successive rain event carves the channel even deeper, making it ever harder for the water to access the floodplain.

What do the impacts look like in our communities?

All of these landscape alterations have changed the way water flows through our watersheds—alterations that are causing serious and sometimes very costly impacts in our communities. This fall, we’ll look in more detail at some of the consequences, problems, and challenges that arise from wetland loss and hydrologic alteration brought on by landscape changes. And later in 2020, we’ll show how with good data, good sleuthing, good design, and good community teamwork, we can bring back much of what’s been lost. Stay tuned!

Photo by Paul Zedler.

Related content

Developing a shared understanding of watershed-based hydrologic restoration

How wetlands manage water

Take a look at how wetlands work together in a watershed to manage water.

Our legacy of wetland loss: Behind our water problems

Fixing the water: Community-led watershed-based hydrologic restoration in Wisconsin