You also know that floodplains provide similar benefits by allowing water to slow down and spread out. In healthy river systems, flood flows spread out over connected wetland floodplains. This natural flooding helps capture sediment, process nutrients, replenish base flow, and more.

Both types of wetlands decrease the erosive energy of runoff during storms by reducing flood peaks. This helps protect downstream roads and neighborhoods.

Understanding the connection between wetlands, flood energy, and erosion is essential for any community interested in identifying and addressing the root causes of flooding and flood damages. Unfortunately, these connections are not well understood or well supported in common flood risk reduction efforts in Wisconsin.

Here’s why: Attention and investment goes towards reducing or recovering from the effects of flooding. For example, federal flood disaster efforts such as the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP) place restrictions on new development in floodplains and compensate insured property owners to help them repair or rebuild after disaster strikes.

The NFIP program, however, does little to address the fact that, in many communities, the lion’s share of the flood damage occurs not from inundation but from erosion caused by flowing floodwater (aka fluvial erosion). This is particularly true in water-rich rural communities where there may be fewer buildings in harm’s way.

Like flooding, a certain amount of fluvial erosion is a natural and necessary process, but it, too, can become unbalanced. Fluvial erosion occurs when flood flows become so energized that they move significant amounts of water, sediment, and debris downstream. This energized and debris-laden water can clog culverts, scour stream beds and road banks, and cause catastrophic failures at or near road stream crossings.

Wisconsin Wetlands Association’s (WWA) work in Ashland County has focused on identifying areas with fluvial erosion hazards such as eroding ravines, gullies, and incised streams. We’re demonstrating how loss of wetland storage contributes to this erosion, downstream flooding, and, ultimately, damage to roads, culverts, and other infrastructure.

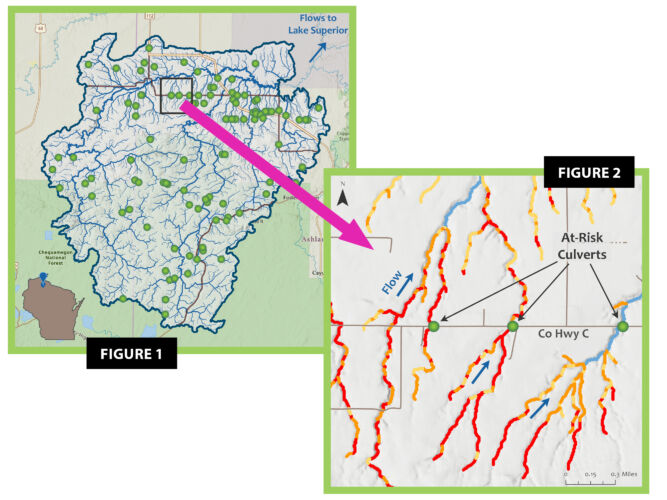

The figures above help illustrate how WWA and our partners are looking upstream to understand downstream flood risks and vulnerabilities.

The first (Figure 1) shows the road crossings (culverts) in the Marengo watershed that are at a higher risk for damage and failure in a large storm event. Many of the crossings are repetitive loss sites, which means they have failed two or more times since 2012.

The second (Figure 2) focuses on one small portion of the watershed and highlights the areas of channel incision and ditching that increase the energy of flood flows above culverts that have experienced or are at risk of repetitive damage. Red and orange channel sections have high and moderate incision hazard conditions, respectively.

As we wrap up the first phase of this work (see here) and move on to the second phase, we’re working to quantify this relationship between loss of storage, flood volume and velocity, and downstream damages. In addition to helping flood-prone communities prioritize areas where wetlands can be used most effectively to reduce risk, this work helps us and partners make the case for looking beyond inundation and increasing state and federal support for nature-based solutions.