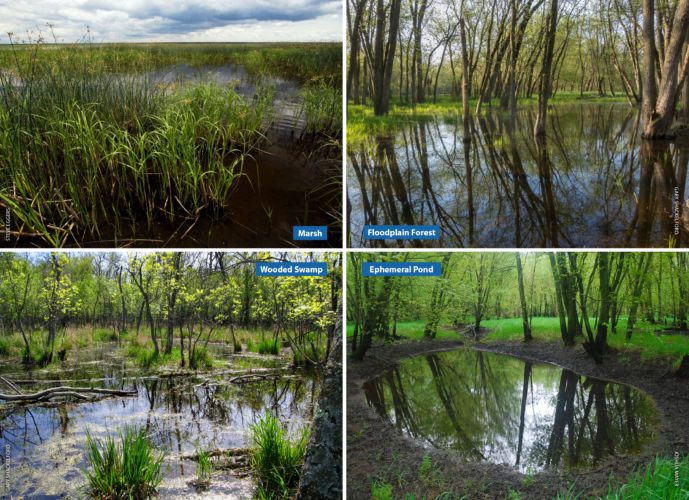

Wisconsin is blessed with many kinds of wetlands. As you get out and about to explore this summer, you may find yourself wondering just what type of wetland you’re in! This is the second in our two-part feature to help you more easily identify some of Wisconsin’s wetland types (see here for part one).

Wetland classification systems are based on soil type, vegetation, and hydrology (the timing, frequency, and level of flooding or soil saturation). While some classification systems divide the state’s wetlands into more than 30 types, we’ll keep our exploration here to eight broad types of wetlands (four in this part and four in part one). Remember, most wetland areas are actually a complex of types.

Bogs & Fens

Heath family plants are common in bogs, including cranberry, bog rosemary, and leatherleaf, as are the carnivorous plants sundew (pictured here) and pitcher plants.

Bogs and fens are uncommon wetland communities with water chemistry (pH) at the extremes: bogs are (generally) acidic and fens are (generally) basic or alkaline. Bogs receive their water from rainfall and snowmelt, and their saturated, acidic soils are low in nutrients. Both open bogs and coniferous bogs are identified by a dense, continuous mat of sphagnum moss. This mat sometimes floats on the water underneath it, and you may feel it bounce when you walk on it. The trees of bogs—black spruce and/or tamarack—are often stunted. In Wisconsin, most bogs are found in the north with a few notable exceptions. Fens occur in places where springs or seeps bring alkaline and sometimes calcium-rich groundwater to the surface. In some fens, white mineral deposits can appear where the springs arise from calcium-rich bedrock. In other fens, the flow of groundwater promotes plant growth that creates a mound over time, creating the unusual situation where the wetland is higher than the drier area surrounding it. Only a select group of calcium-tolerant plants can grow in these conditions, and many of these are rare, threatened, and endangered.

Shrub thickets

Willows dominate many shrub-carrs. Willow catkins (flowers) like this one are often mistaken for caterpillars once they have been pollinated and fall off the tree.

Shrub thickets are wetlands dominated by shrubs and small trees less than twenty feet tall. Periodic disturbances like flooding, logging, or wildfire keep shrub thickets from becoming forests. Typically, the soil in shrub thickets is saturated with water. Alder thickets are mostly found in northern Wisconsin. They often grow along stream banks or between forested and open wetlands and provide high-quality habitat for game species like ruffed grouse, American woodcock, and white-tailed deer. Shrub-carr, often dominated by willow or dogwood, is mostly found in southern Wisconsin. Shrub carrs provide habitat for a variety of wildlife species including many songbirds, game birds like ruffed grouse and American woodcock, and small mammals. Both alder thicket and shrub carr, when in good condition, support some of the same ferns, sedges, grasses, and flowering plants found in sedge meadows.

Sedge meadows and low prairies

Some sedges grow in clumps that create hummocks or tussocks: small mounds of undecayed roots that create microhabitats—and many a twisted ankle!

Sedge meadows and low prairies are open wetlands with dense, grassy plant growth and little bare soil. They are both fire-dependent. The dominant plants of sedge meadows are grass-like sedges that have sharp triangular stems you can easily feel when you roll the stem between your fingers. Grasses dominate in low prairies, including prairie cordgrass and big bluestem. Sedge meadows are often found between uplands and lakes, rivers, or streams. Both sedge meadows and low prairies have saturated soils and are wettest after snowmelt, spring rains, and floods with little or no standing water by the end of the summer. Though once abundant in Wisconsin, sedge meadows aren’t as easy to find today because so many have been drained for farming. Low prairies are found in southern and central Wisconsin and are one of the rarest wetland types in the state.

The combination of uplifting, wave action, and varying lake levels over time created a series of parallel dunes in shallow areas along the Lake Michigan coast, like the ridge and swale wetlands of Door County pictured above.

Rare wetlands

A few rare wetland types don’t fit into the types covered in this series. Interdunal wetlands are low spots (deep enough to reach the groundwater) carved by high winds in sand dunes bordering the Great Lakes. They provide critical habitat for many uncommon plant species and resting and feeding areas for waterbirds. Ridge and swale wetlands have dry sandy ridges alternating with wet areas, topography created over time by varying lake levels, wave action, and departing glaciers. These alternating conditions provide for a great diversity of plants and animals in a small area. Patterned peatlands also have alternating ridges (moss- and sedge dominated peat ridges called strings) and inundated low areas (called flarks). The strings and flarks differ significantly in nutrient availability and pH. Seeps and spring runs are small wetland habitats connected to groundwater discharge.

Additional photo credits: Top photo collage: Steve Eggers (coniferous bog and shrub carr); Gary Shackelford (sedge meadow); Jennifer Webster (ridge and swale). In-story community type header photos: Gary Shackelford (bog); Tara Davenport (fen); Eric Epstein (shrub thicket); Lori Artiomow (sedge meadow); The Ridges Sanctuary (ridge and swale). Plant photos: Kate Redmond (sundew and willow); Gary Shackelford (hummock).

Related content

How to identify Wisconsin’s common wetland types, Part I

Wetland Coffee Break: Swamp, bog, or fen? An introduction to wetland types of Wisconsin

Watch Ryan O’Connor, WDNR, give an introductory presentation on Wisconsin’s wetland types.