Like many of us, I’m not in control of my life. My dog controls my life. So when I’m not travelling around the state immersing myself in wetlands, I live a life under the command of my black Labrador, Cooper. Cooper requires that we frequently visit the dog park near our home—a park that was developed over the top of a landfill adjacent to several hundred acres of crop fields and wetlands. Because the park is an old landfill, the loop trail where we get our exercise occurs on fairly steep terrain that drains down to the wetlands. And because we’re in Wisconsin, this steep trail is affected by a decent amount of rainfall and snowmelt each year.

Cooper insists that I take him to the dog park nearly every morning year-round in all—and I mean all—kinds of weather. As a Labrador, he’s content playing in driving rain, vertical snowfall, blowing winds, sub-zero temperatures, high humidity, and scorching sun. So over the past three years, I’ve been able to closely observe how this particular landscape handles the runoff that Wisconsin weather throws at it.

As I understand it, when a landfill is closed, they seal it, install gas vents, cover it with clay and soil, and plant grass over the whole thing. This can create management challenges when Wisconsin weather shows its face. At this dog park, large gullies have formed on the sides of the property that are fenced off to keep most dogs out (though Cooper manages to find his way in). Of most interest to me, however, are the gullies that form on the main trails after nearly every rain event. Some become quite deep. As I study them each morning, I see the classic forms associated with erosion—headcutting, meandering, material sorting, and sediment fans at the bottom of the hill.

The point of all of this is that my little dog park acts a lot like a hydrologically disturbed watershed. Human-created conditions here prevent the landscape from capturing runoff. This increases the erosive power of the water as it flows downhill, resulting in erosion (gullies) and the movement of sediment downslope, covering the flat lands at the base of the hill. And the poor dog park maintenance crews are tasked with addressing the problems created in this hydrologically-altered mini-landscape by constantly filling in the gullies after each rain event. And like Sisyphus of Greek mythology, they are condemned to repeat this action over and over throughout eternity.

We see Sisyphean (it’s a word, I looked it up) attempts to place temporary bandages on our damaged landscapes throughout Wisconsin. We treat the problems that occur on our altered watersheds without also addressing the sources of these problems. Wisconsin Wetlands Association is working to help increase the ability of communities to apply wetlands as solutions to these issues. Using wetlands and other natural features to slow the flow of runoff upstream reduces the expensive and repetitive repair work needed downstream.

Unfortunately for the dog park maintenance crew, there really aren’t opportunities to slow the flow in this mini-watershed. They do their very best to swiftly patch up the damaged trails, keeping the park safe for Cooper and the other dogs who also control the lives of their owners. Fortunately for all of us, Wisconsin does have plenty of opportunities to heal our landscape, restore our wetlands, and slow the flow. Thanks to your support, WWA is working to turn these opportunities into realities to help heal Wisconsin’s watersheds.

Related Content

Developing a shared understanding of watershed-based hydrologic restoration

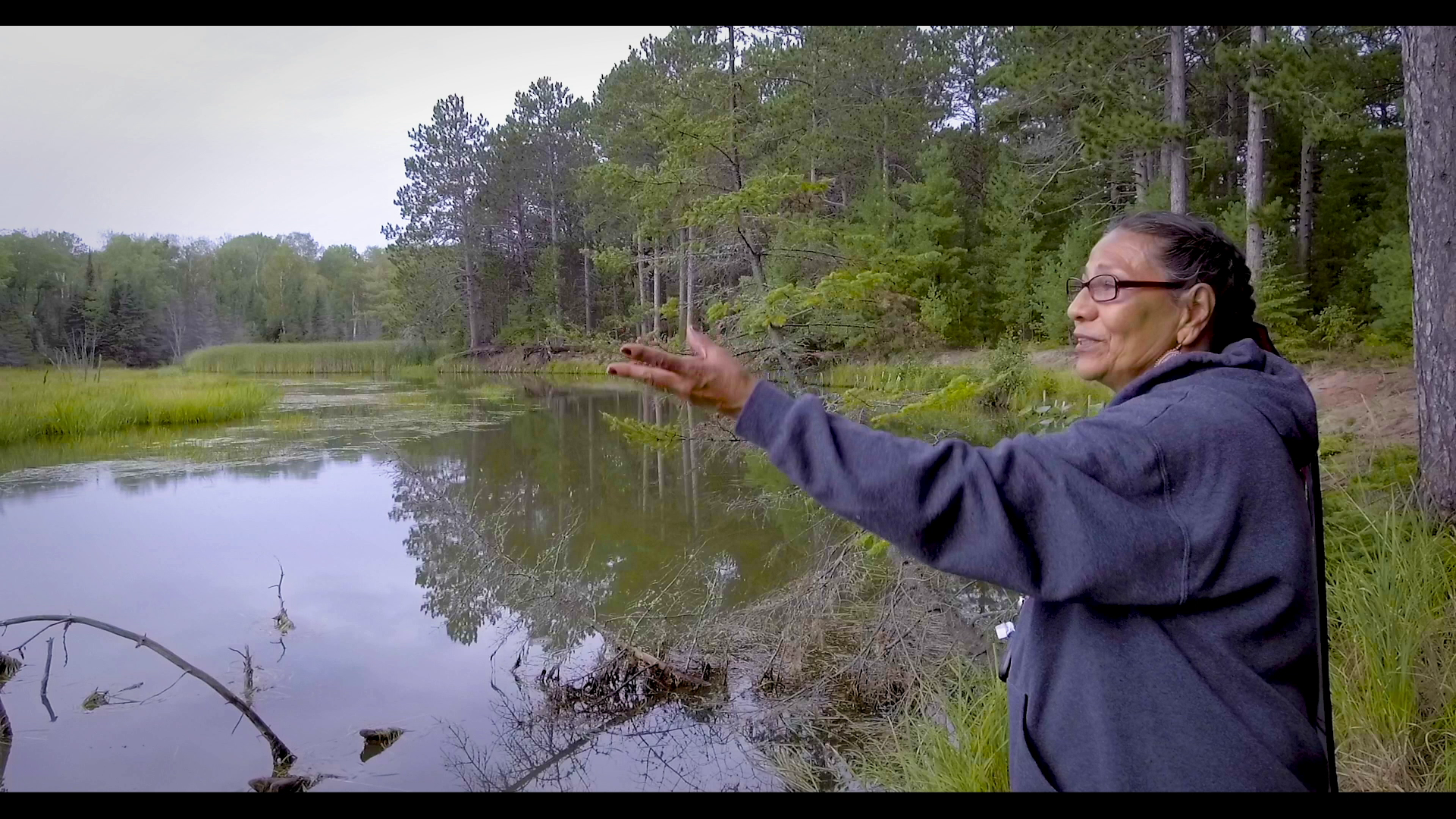

Wisconsin Tribes: Leading the was in protecting and restoring wetlands and watersheds

Tribes in Wisconsin are doing vital work to protect and restore wetlands and watersheds.

From the Director: What brings us together

Want to hear more from the director? Go back with the Director to revisit what brings us together.