Examining the link between wetland loss and flood damage.

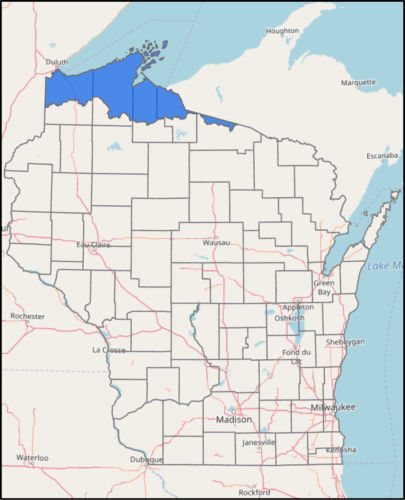

The Lake Superior Basin, shown here in blue, was hit heavily by the July 2016 storm and became the focus of our project.

Between July 11 and 13, 2016, storms dropped a foot or more of rain across northern Wisconsin’s Lake Superior Basin. Two people’s lives were lost and more than $35 million in damages were recorded: highways, culverts, and bridges washed out, and homes and businesses flooded. While storm-related damages are a common problem in the region, this storm was particularly severe

At Wisconsin Wetlands Association (WWA), we have long understood that wetland loss and degradation can affect a landscape’s ability to slow and capture floodwaters. But we had no clear, Wisconsin-based case studies to illustrate the consequences of wetland loss and why wetlands should be an important part of community planning and flood risk management.

As tragic and damaging as the 2016 storm was, it also provided an opportunity to explore the relationship between wetlands and flood damages in the region. With support from the Wisconsin Coastal Management Program, WWA Local Government Outreach Specialist Kyle Magyera coordinated an effort to examine how wetland loss and degradation likely contributed to infrastructure damages in the Lake Superior Basin following the storm.

The basin’s water management challenges date back to the late 1800s when land was first cleared and drained to make way for farms, homes, roads, and more. More than a century of land use changes, combined with erosion-prone soils, have created a fragile landscape prone to flashy floods. To combat the rising flooding problem, regional resource managers have coordinated their watershed conservation activities under a strategy to “slow the flow” to address problems from rapid runoff (i.e. soil loss, erosion, and the delivery of sediment and nutrients to Lake Superior) by installing practices to slow the movement of water.

The July 2016 storm blew out this culvert and the road above it. Kyle is standing at the bottom of the gully created by the flood’s erosive forces of water and runoff.

Though regional resource managers understand that wetland loss accelerates runoff, few communities have invested in locally-led wetland restoration projects to address flood risks. Our project highlights the need and opportunities for implementing wetland restoration practices as part of resource managers’ “slow the flow” strategy.

In a healthy watershed, wetlands protect against “flashy” water pulses by managing water across the landscape. For example, “isolated” wetlands in upper watersheds reduce runoff by capturing, storing, and allowing for infiltration of snowmelt and rainwater, while floodplain wetlands downstream capture and store water that overflows stream or riverbanks before slowly returning the water to the channel.

But the wetland landscape in Wisconsin’s Lake Superior Basin is far from intact.

We launched our project expecting to find a strong relationship between upstream wetland losses and damage to downstream culverts, roads, and bridges, and we planned to produce maps to illustrate this relationship using existing data sets.

We learned that wetland loss and degradation in portions of the basin was far more widespread than the data suggest. Wetlands were being fully or partially drained when erosive runoff carved channels through them. Runoff is also carving streambeds deeper, incising them, and disconnecting streams from their adjacent wetland floodplains, effectively draining the floodplain wetlands. But you wouldn’t know it from looking at the existing wetlands maps.

Our findings are worrisome. The capacity of our wetland landscape to help manage, store, and slow the flow of water is more degraded than we originally thought and it’s getting worse all the time. As wetland storage decreases, the energy of the water flow increases, causing even more erosion downstream. It’s a strong negative feedback loop that renders the natural and built environments of the area less capable of handling rain and snowmelt with each passing storm.

But we also found hope. We found abundant opportunities in the basin to “slow the flow” and reduce flood risks and damages through simple practices to restore healthy wetland and stream hydrology.

The next steps for our project include promoting our findings to increase local understanding of the extent and consequences of the erosion-induced wetland drainage we discovered. We will also be working with interested communities and landowners to install and evaluate wetland and stream restoration practices upstream of vulnerable infrastructure.

With heavy storms and rain predicted to increase across much of the region, efforts like this one are more imperative than ever for helping communities understand how healthy wetland landscapes make them more resilient to floods.

For more details on project goals, methods, findings, and next steps visit bit.ly/floodingcasestudy

Photo by John Buvala of Airfox Photography and Kyle Magyera.

How wetlands protect communities during floods

Let’s put wetlands to work

We need to put wetlands back on the land to help protect our communities from flood events.