Story and photos by Keir Wefferling, Curator of the Fewless Herbarium, Cofrin Center for Biodiversity, University of Wisconsin, Green Bay

On your next ramble out in a fen or conifer swamp, take some time to notice the diversity of textures and colors in the understory! Bryophytes are non-vascular plants such as mosses, liverworts, and hornworts. Bryophytes are excellent indicator species, meaning their presence can tell us a lot about their habitat, like water conditions and substrate pH levels. Despite this, bryophytes aren’t included in regional assessments for wetland quality (yet!).

To help with your bryophyte explorations, here are ten more common moss and liverwort species that you’re likely to encounter in boreal rich fens, northern sedge meadows, and white cedar swamps. Note that while most of these ten can be confidently identified at a glance, most bryophytes are more cryptic—one needs to look for specific morphological features using a compound microscope to be sure of the species (or even genus or family in some cases).

Primer on bryophyte terminology

- Acrocarpous – habit of mosses with minimal branching, upright growth, and producing sporophytes from the top of the plant

- Capitulum – Head-like tufts consisting of clusters of young branches or fascicles at the tip of the stem of Sphagnum

- Costa – The nerve or vein of a moss leaf, sometimes double and sometimes single (or absent), forming a midrib.

- Falcate-secund – Leaves curved like the blade of a sickle and swept to one side of the plant.

- Fascicle – a small cluster of fibers, branches, flowers, or leaves

- Pleurocarpous – habit of mosses with more complex branching (some branched multiple times) and producing sporophytes from near the base of the plant

- Squarrose – Spreading at angles of approximately 90°.

- Thalloid – lacking complex organization, especially lacking distinct stems, roots, or leaves

- Thallus – a plant body without true stems or roots or leaves or vascular system

Pleurocarpous (branched) mosses:

1) Stairstep moss (Hylocomium splendens): this little circumboreal beauty shows its annual growth through discrete steps and can be found in boreal forest and the drier ends of conifer swamps.

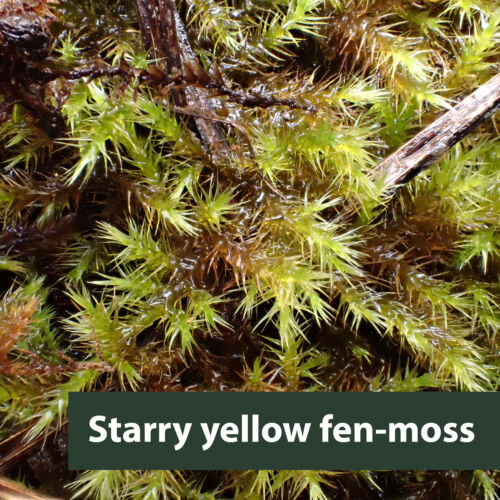

2) Starry yellow fen-moss (Campylium stellatum): you’ll find this moss growing in low, wet parts of sedge meadows and rich fens (fens that are rich in minerals, nutrients, and species). It is recognized by its channeled leaf tips and the absence of a midrib or costa (you’ll need a decent hand-lens to see this).

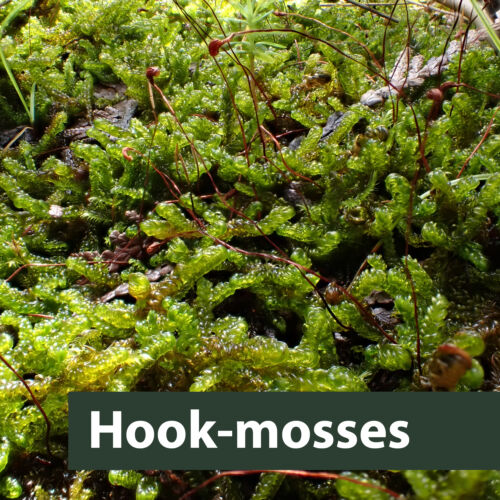

3) The hook-mosses: this group comprises several genera in several families, all of which are indicators of rich and wet conditions. This is a photo of Scorpidium (syn. Limprichtia) cossonii, but this species looks like several other mosses, including Scorpidium revolvens and Hamatocaulis vernicosus. All are recognized by their leaves , which are all hooked and swept to one side of the stem (called “falcate-secund”). These species can be differentiated by microscopic features of leaves and stems. Hook-mosses were formerly all in the genus Drepanocladus and are now sometimes referred to as drepanocladoids)

4) Big shaggy moss (aka electrified cat’s tail moss; Hylocomiadelphus triquetrus): this is a circumboreal species common in boreal forests and conifer swamps. It grows in large swaths and can be recognized by its leaves that are bent out at almost a right angle to the stem (“squarrose”). It is often found with stairstep moss and red feather moss (not pictured here).

Peatmosses (Sphagnum)

While peat may comprise all manner of plant matter (mosses, sedges, grasses, leaves of shrubs and trees, and more), peatmoss is an important contributor to biomass accumulation in swamps and fens. This genus is large, diverse, and often difficult to identify to species. Here are four examples that I often come across in rich peatlands.

5) Magellan’s peatmoss (Sphagnum magellanicum sensu lato): it commonly seen at the tops of hummocks (with cranberry, leatherleaf, Labrador tea, etc.) and can be recognized by the relatively large, hooded leaves and red pigmentation (particularly in the sun). The species complex has a broad ecological niche, growing in hummocks in fens, swamps, bogs, and muskegs.

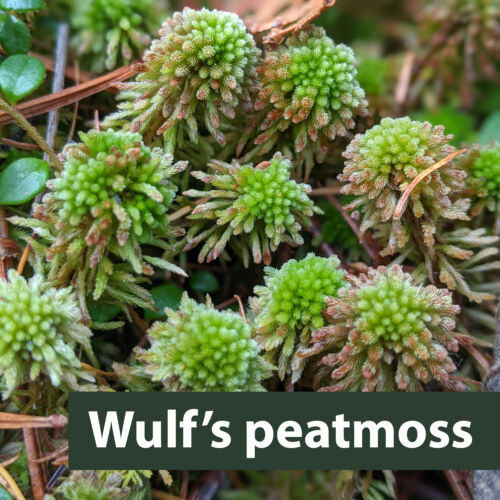

6) Wulf’s peatmoss (Sphagnum wulfianum): a spiky-starry-soft appearance, robust stems, and at least six branches per fascicle (peatmoss branches are grouped along the upright stem in groups akin to the leaves of pine or tamarack). I only see this species in drier microsites within what appear to me to be high-quality conifer swamps.

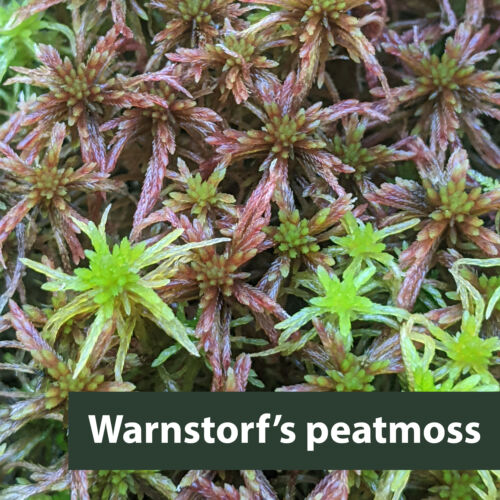

7) Warnstorf’s peatmoss (Sphagnum warnstorfii): our most minerotrophic peatmoss, with tidily-ranked leaves in five rows around each branch in star-shaped capitula (heads) with wine-red pigmentation (best-developed in the sun). This species grows low and wet at the edges of pools and bases of hummocks.

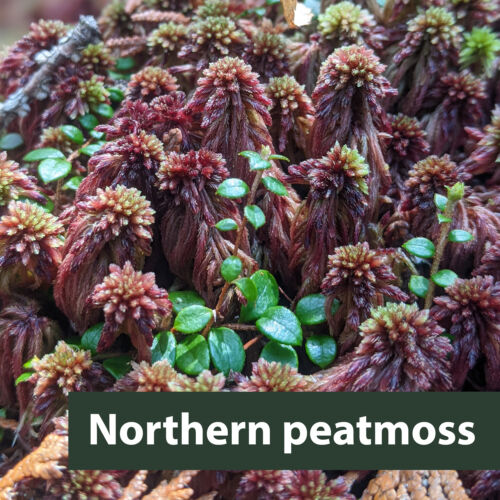

8) Northern peatmoss (Sphagnum capillifolium): this moss is probably more easily identified in the field than in the lab or herbarium. The rounded capitula (heads) and mix of red and green are characteristic and stunning. This species often forms large hummocks around the base of trees and shrubs in fens and rich swamps.

Liverworts

Not all mossy plants are mossy! Liverworts can be leafy or thalloid (lacking distinct stems, roots, or leaves).

9) Three-lobed whipwort (Bazzania trilobata): a gorgeous leafy liverwort having characteristically lobed leaves (mosses almost never have lobed or otherwise divided leaves—examine a few branches to confirm). Search around in a clump of whipwort for the dangling thread-like branches to confirm your ID.

10) Snakeskin liverwort (Conocephalum salebrosum): this species more closely matches common perceptions of what a liverwort “should” look like… but rub and smell a thallus (plant body) of this species and have your concept of liverworts drastically expanded and altered! Folks say it smells citrusy; I say it is the distinctive aroma of a snakeskin liverwort.

I hope that your curiosity about bryophytes is piqued by learning these few. The best way to learn more about these little beings, I believe, is simply to go out and observe them in their home. Get yourself a decent hand-lens (10x is good to start) and a book or three, then go out and observe the forms and colors of the mosses and liverworts (and hornworts, if you’re lucky enough to ever find any!) in your closest peat-accumulating wetland. Before long, you’ll want a compound microscope and some more serious references. Let me know, and I’ll be happy to help you along the way.

Funding for this work was provided by the Wisconsin Coastal Management Program and National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. For more resources, visit: Wetland Coffee Break: Bryophyte floristic quality assessments of Wisconsin peatlands

Related content

Wetland Coffee Break: Bryophyte floristic quality assessments of Wisconsin peatlands

Watch author Keir Wefferling’s presentation on bryophytes that inspired this article!

Wetland Coffee Break: Spectacular sedges in Wisconsin’s wetlands